Micro-Metabolist Home

SHORTLISTED

MICROHOME 2019 - SMALL LIVING, HUGE IMPACT!

International Architecture Competition by Bee Breeders

Location: Tokyo, Japan

Area: 250 sq.ft.

Status: Submitted November 2019

Special thanks to Jeffrey Lui

Emerging in the 1960s, the Japanese Metabolist movement believed that design and technology should reflect the state of contemporary human society, and that architecture could constantly adapt to a community’s needs through regeneration, growing and shrinking like a tree. Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower is a prime example of metabolism, showing a clear relationship between the building core as a trunk and its units as branches. Its concrete and steel construction paired with pre-fabricated individual units designed to be easily attached or removed is a metaphor of spring/fall seasonal changes. Beyond such large scale buildings which resemble trees, there can be smaller residential complexes that resemble shrubs, and in this case of a Microhome, a single small plant.

Besides physical construction, there is also immense value in simulating the internal design of plants. Most plants live on an innate circadian cycle driven by environmental cues such as temperature, sunlight and humidity, becoming active in the day to perform photosynthesis and resting at night. For example, Morning Glory plants begin blooming at 5am and rests from noon. Heliotropic plants even orient their leaves and flowers in the direction of the sun to receive the maximum amount of energy. With big data driving ever-sophisticated climate analysis and smart sensors becoming readily available for household applications, there’s every reason to imagine architecture implementing its own circadian cycles to adapt to changing external environment and personal needs. While the Nakagin Capsule Tower was to be a representation of a changing community over months or years, a Microhome aims to customize and personalize itself to serve the changing needs of inhabitants over hours or for the special occasional use.

Here we strove to stretch the box and explored possibilities in the Z-axis, beyond the limitation of the building footprint. We studied the relationship of the height of a single surface relative to the human body, its best activated use at various heights and its effects on the underlying and adjacent spaces.

OMA’s Maison Bordeaux has a lift platform designed to solve an accessibility issue. The implementation of elevating platforms in our Microhome, together with a series of spatial operations, creates a wide range of functional possibilities adapting to its physical environment and inhabitant needs, elevating living standards.

With the proliferation of home automation technology, the lifted living system is a game-changer with true spatial implications. Compact hydraulic pumps, similar to ones used in car lifts, move platforms to optimal heights according to the external environment and inhabitant needs. For example, in the morning lifts shift platforms into place where sunlight is optimal for a warm breakfast, but shift away from sunlight in the afternoon to cool the room. Pre-set modes calibrate to long-term climate trends, latest weather data, and regular living habits of inhabitants to optimize the living space, while reducing consumption of energy and water for lighting and air-conditioning systems.

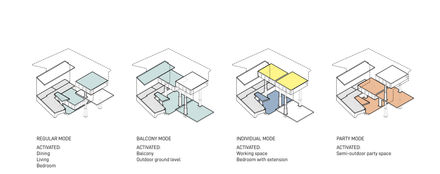

By providing spatial flexibility, Microhomes are most valuable at locations where land is of a premium and every square centimeter matters. While only four options are illustrated here, the lifting system allows for a wider range of platform combinations, creating configurations of space that customize to various needs. Shifting easily from a cosy home to an extended open-air terrace hosting community gatherings, the Microhome’s transformation into different spaces easily justifies its economics.